Thoughts on Print Equation Layout

This will possibly be another piece that will get updates in the future. Actually, I hope not but we'll see. This, above all, is for me. For me to gather my thoughts one (hopefully) last time. For me to deal with stupid garbage which has accumulated over the years. As for you, dear reader, I don't know if this is for you. I didn't write it for the handful of experts in this area; maybe for someone like my former self, back when I started writing mathematics on the web. Maybe for someone who knows the web and wonders what all that fuss with equations is always about. In any case here's a fair warning: I'm not going into every detail so if I lose you along the way, remember these first few lines and go do something more fun, it's fine. Just don't be that guy (and it's invariably a guy) complaining about free stuff on the internet.

This is also a lamentation. Nothing I write will change anything of what's to come. It is also (hopefully) a bit of mental cleansing. A few years ago I had strong burn-out symptoms due to working in this (as it turned out toxic) field. It takes a lot of effort for me to not be dragged down again. But one last time I want to try to write up where I've arrived after thinking about equation layout on the web for over 10 years now.

If I make a claim without substantiating links, it's most likely to avoid more burn out; you can ping me privately though. If I'm giving just one or two examples, it's not because that's it but because this piece is very long already. [If you want deeply detailed research results, feel free to contact my company - we do that kind of thing.]

Finally, I thank the kind people who read this piece before I pushed it live - your feedback was invaluable; I owe you one.

Introduction

10 years ago I joined the MathJax project which forced me to think a lot about how to put equations on web pages. Actually, I had already spent quite a bit of time during my PhD and postdoc years thinking (*cough* procrastinating) about the same thing, albeit from a different perspective.

When I started writing on the web all 13 years ago, I quickly went through a phase I've seen repeated by many people since:

"oh, there's something called MathML, I should use that"

followed by

"oh this does not work at all, let's not use that",

usually followed by choosing jsMath (if you're old enough) and later MathJax because they ultimately remain - by far - the best tools for the job.

After joining MathJax, my job was to profess the prowess of (read:blindly advertise for) MathML, so I did. That was largely because MathJax was formally part of Design Science at the time and they made money with MathML. Luckily, the project moved to the AMS where we could think about things more freely.

When the whole Chrome 24 debacle happened, there was this one comment from a Googler (on Google+, naturally you might say). I can't find it anymore but what I recall them saying is: "maybe it's a good format but still a bad format for the web". I kept coming back to that thought for a few years and, eventually, came to agree with it. (This piece is basically summarizing that.)

In short, I realized that MathML is fundamentally a useful XML print publishing tool but a bad technology for the web. So I tried to pivot MathJax away from MathML and its toxic community towards actual web standards and their underlying principles. We wrote a whitepaper, got our sponsors on board, and started work on MathJax v3. (This is not what v3 became but that's ok. I left my position at MathJax around the first beta which was a thrill and I'm grateful that Davide and Volker enabled me to leave with that big leap forward having begun.)

Towards the end of that period, I wrote a number of pieces here, outlining MathML's many flaws and failures. But as I kept writing: it's not MathML's fault. MathML does what it's supposed to; but what it's supposed to do is a bad fit for the web. (Again, this piece is basically re-iterating those pieces. What do you expect from a recovering academic.)

In the past 5 years, I've worked primarily on the issue of converting full mathematical (LaTeX) documents to web formats. If you follow me on the fediverse, you may have seen me use the CW "TeX in real world production" sharing some of the "gems" from this experience.

All of this has led me to realize that there's a "deeper" problem and I feel like it needs a (sort of) new name: print equation layout.

Framing

Framing is important. What I call "print equation layout" is more frequently called "math layout", "formula layout", or just "math" (I find that last one somewhat insulting). The phrase "print equation layout" may seem unnecessary or convoluted. To some degree, I agree. For example, I don't believe we have seen "web equation layout" come into existence during these first 30 years of the web. Nor, sadly, do I expect to see it in the next 10.

But as a framing device "print equation layout" serves to ground the conversation and keep aspects in focus that I find critical to many discussions.

In my opinion, print equation layout is, ultimately, a flawed print tradition that web technology should not have to make extra efforts to support (e.g., as proposed by MathML's addition to HTML5 way back when). The layout features are largely archaic with very few actual challenges remaining in the context of contemporary (2022) web layout.

Furthermore, print equation layout is fundamentally inaccessible in the sense of web accessibility. However - and this is where this part gets very tricky - print accessibility traditions for print equation layout do exist (at least in the US as well as a few other countries and of course the US perspective always dominates these conversations). This may seem like a contradiction - how can there be an accessibility tradition that is bad in the context of the web - but it is really no different from the visual layout traditions.

This is a key complication in the discussions (and myths) around this topic: because print layout and print accessibility traditions exist, people assume that they must be realized on the web - and in the same way.

I want to argue that neither aspect of print equation layout - visual layout traditions and accessibility traditions - is particularly good or useful on the web. As a result, it is a particularly problematic set of techniques because the contemporary web already has plenty of good and useful features that solve print equation layout.

Adding an additional, separate feature layer for a problematic print technology tradition does not make any sense, in fact it has a (by now long) history of hurting the community.

Interlude

In TeX, we can put punctuation after a table. In HTML, we cannot. Should HTML change because this print tradition exists?

What's in a word

Let's try to be a bit more specific.

Print equation layout is...

- what people think of when you say "math/formula/equation" // what MathML partially captures // what math mode TeX usually produces // what MS Word formulas usually look like

- an elaborate, two-dimensional form of abbreviated notation for compressed, highly complex, context dependent, abstract thought.

That's a bit of a mouthful, I know. But, in the spirit of recursion, this compressed, complex description captures the essential problems well and much follows easily from it.

This is also not an observation of edge cases, it holds at an elementary level, e.g., in the shape of long addition/multiplication/division or "explanatory" annotated layout in school-level material. At the research level, things are much (much) worse, because research by its nature invents new concepts but more so because especially compression was exacerbated by the content explosion of the 20th century, combined with print page limits.

A first consequence of this description is that print equation layout is highly ambiguous because the compression is very lossy. What's worse is that print equation layout not just needs context but is frequently integrated into other complex notation (e.g., text annotation or graphical documents).

A consequence of this is that it is "non-text content" (in the sense of WCAG SC 1.1.1). It is much closer to "ascii art" than HTML traditions of "semantic markup" with concepts such as heading, landmark, or widget.

Naturally, this does not apply to all instances of print equation layout. It crucially applies where the actual problems occur - both in visual and non-visual rendering. The problem is not to handle 1+1=2 (well, actually we'll get back to this), the problem is more like:

This is a simple piece of print equation layout, something from the first few months at university. And it is packed.

interlude

Cars are a bad technology.

They need massive resources to build, most use fossil fuel to run, all need massive infrastructure, destroying our habitat; they are vastly inefficient, they stress people out, they fill our streets and sidewalks with megatons of metallic monstrosities.

And yet most people own one or want to own one. They have their uses, some at which they excel. So they're here and we need to think about them.

But that doesn't change the fact that we should think about a world without cars because it could really be a much better world for everyone. And we shouldn't insist to keep building our world around cars or make cars a core assumption in our "cultural stack".

The same holds true for print equation layout.

Visual print equation layout on the web

practically

The problem of realizing print equation layout on the web has been solved for almost two decades now. Well, 18 years to be exact.

Let that sink in for a bit. 18! years!

With CSS, this solution started as (client-side) JS only and span soup; we have had that since 2004 (via jsmath, MathJax's precursor).

With SVG, we've had this since 2011. MathJax v2, at first client-side but quickly also server-side (via phantomjs and later via nodejs). [To some degree, various tools could produce SVG from, e.g., TeX, even earlier that but they didn't generally care about the web as a use case, e.g., they wouldn't give you good vertical alignment to meet a baseline.]

It has been possible to realize print equation layout with just CSS (e.g., server-side generated span soup and CSS) since IE8 - IE8 dammit, released in 2009 - and with just SVG since IE9 (2011). [To be fair, MathJax was not the first to realize such a CSS approach, KaTeX was, but one of my favorite successes while at MathJax was to prod Davide long enough about a "fast Preview without JS" that he built the "CommonHTML" output for v2.7 which added this. I'm also still fond of the previewHTML output which preceded it and traded beauty for CSS simplicity.]

Visual print equation layout has been solved thrice over with a myriad of smaller and larger tools doing it in varying ways, balancing code simplicity with quality of layout. (mathquill, jqmath, math-ml etc)

[Aside. This is why a certain blog post from a few years ago about "alternate timelines" was so very much off base - CSS driven print equation layout was first, SVG a close second, not some XML dialect nobody was using for anything but print production. (And no, IE plugins do not count in my book.) In the similar situations the same people would (indeed did famously) argue that working solutions should be considered the prime candidates to move standardization forward, not some contrived academic proposal. But I digress.]

So print equation layout solutions for the web have existed for a long time.

Are they perfect? No.

Are they still getting better? Emphatically yes - all the time. The ever evolving CSS continues to make things easier (grids, container queries, variable fonts, layers!). SVG is just rock solid (for these purposes; and it improves, too).

The most significant CSS challenge at this point are stretchy character constructions - not a massive problem and one that could (and should) be solved independently of any "mathematical" considerations since stretchy constructions are frequently used in other design scenarios (e.g., stretchy braces around lists are pretty common design patterns).

In the nice-to-have category, I'd place better control over glyph bounding boxes. Right now, high quality print equation layout realized with CSS depends on webfonts. This is not a particularly critical consideration in my book - much high quality text layout on the web relies on webfonts - and the bounding box problem also needs a more general solution (and in fact there are proposals for better access to font internals).

Some people argue that the CSS and SVG layout solutions like MathJax generate "convoluted" markup output. This is a red herring.

On the on hand, convoluted XML is not "better" if it says "math" in it. On the other hand, nobody from CSS or SVG (spec) land has ever tried to help so tools in this space make do with what they can find. My favorite comparison for web people is: the output looks a lot like Bootstrap's grid layout in its early days (somewhat convoluted) or an accessible datepicker markup today (extremely convoluted). In other words: it looks the way it looks to get the job done with the tools available. And it does. And it gets simpler every year.

If print equation layout tools for the web were heard the same way grid frameworks were heard way back when, we might get simpler output even quicker and in a way that benefits the entire web stack. In a world of div-soup SPA's I think the "ugly output" argument is entirely a red herring.

interlude

From Oral History of Butler Lampson (Interviewed by:

Alan Kay) (via Robin Sloan's newsletter)

Alan Kay: But I wish that you had been at CERN on a sabbatical when [the Web was being born].

Butler Lampson: I probably would have been a disaster.

Kay: I don’t know. But I think you would have made a slightly better …

Lampson: No. No. No. No. No. No. What Tim [Berners-Lee] did was perfect. My view about the web is that it’s the great failure of computer systems research. Why did computer systems researchers not invent the web? And I can tell you the answer. It’s because it’s too simple.

Kay: It is too simple.

Lampson: If I had been there I would have mucked it up. I swear to God. The idea that you’re going to make a new TCP connection for every mouse click on a link? Madness! The idea that you’re going to have this crusty universal data type called HTML with all those stupid angle brackets? We never would have done that! But those were the things that allowed it to succeed.

theoretically

Ultimately, the problem is: is this layout tradition a good fit for the web platform? Take table layout. At first people thought it was a good fit. Now we don't.

I think print equation layout is a thoroughly bad fit, building it into the web actually damages the platform, just like tables have taken two decades to become unscrewed (oh hi Google, still using tables for layout in some products).

Even for the simplest examples we run into "fun" print equation layout traditions that are problematic. The easiest to understand are the many text-dependent behaviors, i.e., layout behavior that changes depending on the specific text nodes present (beyond the obvious layout changes from having different text nodes).

The simplest example is probably: single letter variables are italic, multi-letter ones are upright. This is pure tradition, i.e., something a lot of people like to do. Obviously people sometimes don't do this. Obviously, there's no technical difficulty to make this happen as an author / authoring tool on the web today. But as a feature for the web it is weirdly different from any CSS/text rendering features we have; that's just not how styling text works.

A more complex example are moveable limits. For example the TeX expression \sum_{i=0}^\infty would, at plain view, indicate we get a summation symbol with a subscript of "i=0" and a superscript of infinty.

However, this depends. As an inline expression, TeX will lay this out as I just described.

However, as a display/block expression, the sub- and superscripts will become under- and overscripts.

Most print equation layout systems have similar mechanics. This is of course convenient from an authoring perspective - you can switch modes as you like, thus macros or copy&paste are much easier to do.

However, from a web design perspective it is a wild thing. Not the change as such (of course children change when a container switches from inline to block). But when you replace \sum with something else (say an "S" for "sum"), you will suddenly not get this behavior anymore. It's driven by (an allow list of) text nodes.

From a layout perspective, this automatism wouldn't have to be builtin - you have to have tooling to specify both layouts anyway - yet MathML, as a print equation layout system, builds it in. This means, we have intentionally ambiguous layout instructions that change rendering depending on text content. This very weird from the perspective text layout on today's web.

From this we can take a step up and talk about the operator dictionary. Remember when I spoke about 1+1=2 not being the hard problem. Guess again, we made it hard!

[I mean, what do you expect? There's a reason why movies will visually indicate something is difficult beyond comprehension by showing print equations layouts; even memes about confusion get more popular when you add equations to!]

Naturally, there are traditions around how you space things. 1+1=2? 1+1 = 2? 1 + 1 = 2? Or something more subtle? There are many traditions like this, the most well known being Donald Knuth's as captured in the TeX book.

But that's just it - they are traditions. Traditions, based on Knuth's review of Western (and mostly English language) publications from the late 19th and 20th century.

And people can, do, and should deviate from traditions. If there's one thing I've learned working in mathematical publishing production, it's that authors are full of ideas for how these traditions should change (most are bad, some are genuinely good, sometimes the worst ones are the best).

I mean, look at this weird theorem layout from 1940:

Thank goodness that style didn't catch on.

Instead of giving them the tools that allow adjustments, most print equation layout systems (and MathML in particular), only hand them spacing hacks. This may be fine for print where, in the end, you just want to put some ink on a canvas and no one can see your hackery. On the web, the structural damage is apparent and causes numerous issues (e.g., performance, accessibility). Compare this to CSS where we have benefited from a system that allows resets and customization clearly and cleanly; in comparison, a paradise of tools for designers, authors, and developers.

None of this is to say that there aren't interesting aspects of print equation layout that are worth a look for the web; something as basic as multiscripts or something as complex as stretchy glyphs. But bringing them in a way that drags the baggage of 100 years of print equation layout along is an obviously stupid idea (that can be explained but hardly forgiven).

Stretchy characters are also a weirdly terrible tradition: to stitch together glyph pieces to form something else. Of course it makes sense in a print setting - you work with what you got (just like you re-use typefaces left right and center). But what do people use stretchy character for? It is actually a very simple concept: a border. Yes, the specifics of the border style may carry some (contextual) meaning, but that's the case with most borders in general. The main layout purpose is very specifically to separate a chunk of layout that benefits from a border on some sides of its box. That's all there is to it. It's even in the name: these constructions are commonly called "fences" (mathml 3 even has an mfenced element, may it rest in pieces). A fence is a separator (ARIA pun intended), something to mark a border.

The MathML people want the ability to build stretchy characters to be limited to internal magic of MathML implementations in browsers, relying on low-level access to Open Type MATH tables without doing the hard work of surfacing this complex technology to userland. This technology has a somewhat problematic history in itself. The extension was developed by Microsoft exclusively for Word and only years later proposed to Open Type properly to help, really, the MathML people to make the case that "it's a standard". There are only a handful of fonts with MATH tables around because they are quite complex (read: expensive) to create.

Even ignoring the troublesome history, this approach limits a rather lovely concept used throughout design (just search dribble or codepen for curly braces) to supposedly "mathematical" markup and layout. It is quite silly especially since even basic uses case won't actually be possible this way (e.g., a stretchy brace around a list would still be invalid, even ignoring "semantics"). Any which way, we still need an alternative.

So why not rethink this in the context of the web? Why carry over a silly tradition (which is actually even worse: fonts will have multiple sizes of fences and those will be used if the box they wrap around is small enough). We have so many useful ways to indicate that something is grouped together on the web, we have traditions around those too (e.g., hover, focus, target effects, easily shaded or animated backgrounds to indicate depth), some of which are problematic for other reasons. We have a dynamic medium that allows you to only expose the gnarly information like this when a user actually requires it instead of on-the-nose all the time. We can also leverage the web's infinite canvas to build new traditions that serve users better. For example, stretchy braces do not increase by just nesting. They stretch only to match the contents, thus in a double parentheses situation (like ((...)+(...))) they will not grow, thus not actually represent the full complexity. That's understandable in the limited, fixed page sizes of print products. It also forces authors to do silly hacks to get additional dimensions should they want to communicate differently than tradition allows for. Maybe authors on the web want to do things differently from the web?

And of course it's funny how even if you insist on a fonts-based alternative there's already a solid alternative to build upon today: variable fonts can do wonderful stretchy things and can obviously solve this problem. Just without magic and with control in the hands of authors.

If you move away from the silliness that you need to reproduce print tradition, you'll find that you can solve more problems. For example, asymmetrical or partially colored stretchy constructions. It's perfectly reasonable to have a \begin{cases} environment but want the part before it on the same line as the first case. You can't do that with Open Type MATH tables. You can hardly do it in TeX.

The operator dictionary is another good example for this. Doing layout based on text content is an interesting topic - we've had years of debates around aligning table cells at decimals. For trivial spacing changes around elements - which authors want to customize anyway - it seems just a bit silly.

As related and similarly bad example are math alphabets. They are pretty mad to begin with; they are fontface traditions, captured as Unicode codepoints. It's understandable that mathematical writing and print traditions have abused fontfaces - it was a nice hack when all you have is moveable type. Enshrining them in Unicode does make some sense for print because (in a twist that should not be a surprise) it turns out that these glyphs have grown their own requirements. For example, Greek character glyphs tend to need special shapes for mathematical context than for Greek texts. In the mash up of technology limitations that is print equation layout these glyphs serve contradicting roles: be identifiably different but fit nicely with the Latin glyphs. This leads to really weird design quirks, see for example From Unicode to Typography, a Case Study: the Greek Script" by Yannis Haralambous (tip of the hat to Christian's wonderful Interesting Esoterica).

The recent addition of math calligraphic scripts to unicode (while unsurprising given the people involved) is weird to me because authors will not and do not stop. The other day, we had a paper with runes come through production. Should they add "math runes" to Unicode next? And what about David Griffith's script r, does he get a codepoint all for himself? What about math emoji? Also, what about math alphabets when they're in text mode - do they have special meaning, too? (Other than making horribly inaccessible social media profiles, that is.) More seriously, I'm not aware of any discussion of how the math alphabets are purely focused on supporting authors using the Latin alphabet. For lack of expertise, I have not written about non-European print equation layout traditions because I know next to nothing of them but from the little I know (e.g. the ancient W3C note on Arabic mathematical notation) I suspect they might make for an interesting post-colonialism study. [Aside, there is a direction where I could see Unicode actually help, just like it does with emoji: codepoints for actual mathematical concepts that are usually represented as a single grapheme. Indeed, the history of some math alphabets hints at this, e.g., the few blackboard bold symbols that are in the Basic Multilingual Plane. Just like we have a heart and a heart as card deck suit.]

It is worthwhile to note at this point that in recent years more and more TeX users (including the AMS) have been leveraging a re-interpretation of Knuth's rulesets by adopting xelatex which realizes equation layout using Open Type MATH Table fonts which, again, was designed for Microsoft Word when they built their print equation layout facilities alongside a first font from Tiro. While Microsoft and Tiro followed the TeX book there are noticeable differences, making it hard to know if the bug is in the font, in MS Word, or in xelatex.

On a slightly higher level, we have traditions such as labeled equations. They are surprisingly complicated in themselves. For example, most systems will provide authors flexibility in aligning or auto-numbering them, they may be mixed with other constructs (such as stretchy characters, e.g., in the LaTeX package cases or empheq). In some print equation layout systems they'll be realized via table-like constructs, in some via lower level primitives (horizontal fills, floats etc).

It also gets complex when you look to integrate equations into surrounding content. Print (equation) layout systems tend to treat equation layout as starting an entirely different context; the break is fairly absolute, both for inline and block layout (albeit in different ways). This doesn't fit well with the web's DOM and CSS's box model however. For example, equations tend to have break out of all context and align to some global property, in particular their labels. So a block equation in a list will simply break out of everything and potentially place a label at a far end of the line. This fits very badly into the web's layout model(s).

Next step up you'll find alignment across equations. A common feature in print layout engines with equation support (e.g., amsmath's intertext). Should we enable these kinds of traditions? Maybe; I do think this last one is fascinating. Should we do it by replicating print (equation) layout traditions? That sounds rather ludicrous to me.

Another problematic print tradition lies in inheritance. Traditionally, print equation layout will work as a reset. E.g., in TeX math mode will not inherit surrounding text styles or weight. Why? Well, because that would change the "meaning" because you're abusing style and weight: if you use a normal V and a bold V for two different concepts, then naturally in a bold heading you'll run into trouble. On the web, we see other traditions to surface; for example, people find it very irritating if a fraction is not bold inside a heading. A very real problem happens if a link starts or ends with print equation layout which is suddenly no longer styled like a link (e.g., neither blue nor underlined). That's a real problem for users (and possibly failing one or more WCAG SCs). Purists will insist - and they are wrong, at the expense of users. [Fun fact: that's why I personally prefer SVG with paths instead of characters/glyphs when reproducing print equation layout on the web. It's more honest to the print content tradition and happens to avoid many of these problems with ease.]

Of course there's yet another exception. In TeX for example, when you nest text mode inside math mode, that "inner" text mode can inherit. This means text in a piece of equation layout ends up, say, italic if the text surrounding the equation layout is italic (e.g., in a definition). Does this lead to confusion? You bet.

To recap

The problem of creating visual layout that matches print equation layout has been solved for well over a decade. It's somewhat ridiculous to suggest the web has a significant technology gap here that only a completely new set of markup and layout features can fix. Additionally, the theoretical structure of print equation layout enshrines problematic traditions that fit very badly, going against the web's grain.

This leaves non-visual-layout considerations regarding print equation layout, in particular (web and print) accessibility considerations.

Ambiguity

Let's talk about ambiguity.

A different example

To start, consider a different example, musical notation. In modern notation, a note is about as ambiguous on its own as a grapheme in text. For example, without a staff and other context the note itself doesn't tell you much. You might know the value by looking at just the note but even then this might not be enough (e.g., if you happen to miss a subsequent dot or preceding accidentals). Even with a staff, you might still have trouble, e.g., if all you have is a single measure you might lack the key. Similarly for dynamics. Also, it might be part of music that ranges from Opera to Jazz and you'll want to know that to adjust your understanding.

It's hard to know when you have all the relevant information. A piece may appear complete but lack information on, e.g., which instrument this is for, what other voices there might be.

And this is for a fairly limited set of notational elements.

Now expand this to the ever changing mathematical notation, then expand to engineering and sciences where there is no limit in generalization and specialization. [Of course, musicians can easily discuss a single note as passionately and intricately as mathematicians discuss a single number. But while this is much more interesting, it is unfortunately not the topic here.]

Some examples

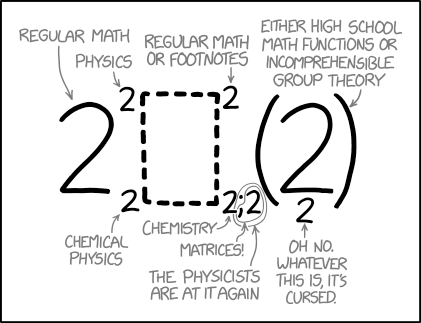

- a superscript 2 (e.g.,

) - is probably some sort of "squared" thingie? But is that always true? How about or ? - a binomial coefficient cannot easily be distinguished from a 2-dim vector notation -

vs ; similarly for Stirling numbers. - frequent use of space or punctuation to imbue layout with extra meaning or to avoid having to add clarifying notation (e.g.,

+a + -c + +bvs, say,++bhttps://whystartat.xyz/wiki/Space_is_significant)- "(a,b)" - open interval? point in the plane? bilinear form in a Hilbert space? - punctuation in general. If it's in the middle, is it just a separator as in

or an operator as in or ? If it's at the end, is it part of the equation or actually text (a common sight in block expressions) [a]might be the sign of a //[c, d]might be a matrix //A[b]might be a ring|...|- absolute value, norm, determinant?|- evaluation of definite integral (alternatively[ ... ]but that could also be a closed interval or a commutator)- what is the difference between

and and how would you find out? - superscript -1. Is it an inverse? A "1 over something" ? A reverse operation? Some kind of transposition? An index for something enumerated by integers?

- "d" in

vs "d" in - uppercase delta

and the triangle symbol can look surprisingly similar depending on the font. - invisible operators (U+2062, U+2061) - where to even start?

For more "inspiration", check out https://whystartat.xyz/wiki/Category:Ambiguities

An absolute favorite of mine is the Legendre symbol

We can also go the other way around. We can have the same voicing for different notations. |A| and det(A) may read "determinant of A"; both exp(x) ande^x may read as "exponential function at x". How would a non-visual user know which notation was used when someone said this?

A separate problem are the math alphabets, i.e., the abuse of using typefaces to identify different, context-dependent concepts. It seems so easy to - visually - discern italic from normal, serif from sans-serif, gothic from Sütterlin - well, in truth it is not that easy but here we are anyway. In addition, foreign alphabets are abused so much that mathematics has become reliant on particular typeface designs as mentioned earlier.

For non-visual users, these then have to be differentiated (otherwise you're no better than a "read more" link) and the noise ("Upper Gothic X") is immense - or more often: the silence is immense.

And then we haven't even opened the box of notation that's specific to engineering, physics and chemistry but realized using print equation layout.

Semantics or layout?

There's a moving goalpost (or perhaps gaslighting) issue that I've encountered many times: should assistive technologies (AT) provide information about layout or semantics when it comes to print equation layout?

A common stance in the general accessibility community is: it's not about special treatment, it's about equal treatment. What does that mean for print equation layout? Equal treatment would provide precise information about layout.

But that's not what users actually expect (or are accustomed to). Instead, "semantics" are desired. Take this simple example:

f: X → Y

Should it read

"lower italic f colon upper italic X right arrow upper italic Y"

or

"f maps from upper X to upper Y".

The latter is certainly easier and happens to be how humans speak.

However, print equation layout does not offer such semantic information. Therefore, solutions turn to guesswork aka heuristics.

These heuristics work barely for school-level print equation layout and some, more "stable" parts of college education (e.g., engineering). But they easily and frequently fail even in these areas.

To come back to our examples: yes, that superscript 2 is very likely "squared" but then again it is, inevitably, far from always "squared". As usual, xkcd has you covered on the subject of "2" (cc-by-nc 2.5):

Beyond the evident lack of semantics in print layout per se, the second problem is the lack of contextual information. While MathJax and its sister project Speech Rule Engine did some Simons-funded research into the problem a few years back, no existing solution takes even other equations into account (e.g., using the guess for a variable that was used earlier).

Heuristics definitely do not try to analyze the whole document context to trigger specialized heuristics despite the many obvious advantages. Just by field, you can differentiate a lot -

The simplest examples can show how tricky this is. Think about f(g+h)(x). You might agree that there's a good chance that there's a function application (at x) happening but it could also just be a multiplication with x after some calculations within the parentheses, who knows. Fairly limited contextual checks can probably help out here but without them we're lost.

What's worse: today's heuristics also often do not work within an equation, e.g.,

Speech Rule Engine's heuristics (the best around) will identify the middle part as a matrix determinant but still treats |A| as absolute value. And in fairness, if we didn't have the first part, that A might still be some poorly named scalar.

A key feature of the heuristics is surprisingly boring and complex: grouping things. Where do subexpressions start and end? Since print equation layout is inherently non-semantic and built for author convenience, most authoring does not (have to) care about grouping the structure well. Who cares, you'll work it out visually and from context (thanks, PEMDAS!).

Here's a pretty normal, real world example:

Note how the parenthetical expression starting after Re ends in another table row. This is perfectly understandable authoring from a print author perspective - your line is fixed and limited, you'll need to break things up. Since you're in print (and you want alignments to work), you push pieces into a table.

How should heuristics work out this grouping? The answer is: probably not.

Another interesting example is the treatment of horizontal and vertical space. "Clearly", if you find $(a \quad b)$ and $(a\ b)$ near each other, they're different, right? But what can heuristics realistically do here? Especially, when they only work on a single expression? [Aside: I give the source here - SRE would indeed give the same descriptions for these expressions.]

Print equation layout uses positive and negative space abundantly and often confusingly. Some authors like things spaced out where others like them tightened up. This makes it impossible to leverage space in heuristics. As a consequence, space is not to be messed with. [This also creates problems if you're mistakingly thinking print equation layout is text - because WCAG 1.4.12 would then force you to allow users to change word and letter spacing. In the end, space is significant.]

Similarly, one of the most important visual tools is completely absent from non-visual presentation: the size of stretchy glyphs. This is sad because the whole reason we use stretchy constructions in the first place is to make layout more accessible for users. Stretchy constructions indicate both grouping and the complexity of subexpressions. Authors frequently use it to explicitly highlight subexpressions because they realize their complexity. And yet despite their focus on layout, non-visual presentations provide no access to this information; there is no representation of stretchiness let alone the relative dimensions. The most you can hope for is something like Speech Rule Engine's ability to summarize a subexpression (along the lines of "a sum of 16 summands"). Good grouping informs users but there's a significant benefit to a stretchy character: the larger it is, the more crap is going to be inside whatever it groups - to the point where they can be downright scary. They are critical information.

Frequently, people (especially in the MathML community) promise magical semantics from print equation layout. Yet when faced with the obvious, plentiful, and unsolvable problems, the goal post is casually moved to "you need to give layout information" only so that when you provide layout information, people go back to "oh, that's not the idea, you should provide semantics".

Unfortunately, many people believe this empty promise.

Problems from print layout traditions

There are both theoretical and practical problems arising from print layout tradition.

Theoretical

Besides the fundamental issues outlined above, print equation layout has some traditions that add another layer of problems.

For example, we go back to the concept of moveable limits. The expression

\sum_{i=0}^\infty

would, at plain view, indicate we get Σ with a subscript of i=0 and a superscript of ∞.

However, as you might recall, this depends on the mode. In inline math mode, TeX will lay this out as described. In display math mode, the sub- and superscripts will become under- and overscripts. This is, again, convenient from an authoring perspective - you can switch modes as you like, thus macros / copy&paste are much easier.

This automatism wouldn't have to be built into a system from a purely functional/layout point of view; it's authoring convenience. Of course, MathML builds it in to be compatible with print equation layout traditions for which it was designed. In fact, it adds the (ever growing) operator dictionary to describe various layout rules like this instead of focusing on just the necessary parts of layout.

This means, we have intentionally ambiguous layout instructions and that's tricky for heuristics to work - yet another context to check. [For once, that's not terribly weird for the web but media and container queries separate this much more cleanly - and they are separate from any semantic interpretation.]

So what do heuristics with such ambiguous layout? They cheat to make this ambiguity go away. When voicing, simply say "sum from ... to" - tada, problem solved! Of course now you have 3 new problems: a) what if it isn't a sum? b) what if it is a sum but using a different character for the summation operator?c) what if the authors want to use side- and overscripts to mean different things?

Practical

Given the nature of print products, authors are prone to abuse layout instructions. In the end, it has to look good, who cares how they got there.

For example, authors frequently make their content work purely visually, placing elements side-by-side, relying on the fixed positions of print layout.

They will use table layout to split content apart so that it can fit page dimensions (e.g., complex breaks across lines), thereby making it impossible to reflow in a dynamic environment and group correctly in anon-visual semantic analysis.

Reversely, they will space content out to fill a page, impeding reflow or resizing in dynamic environments.

They may "accidentally" rely on TeX's defaults, e.g., consecutive display math blocks may align if those blocks are generally centered (rather than explicitly grouped by aligned blocks); yet with different alignment defaults, the alignment may fail unexpectedly. Similarly with multi-line environments or other manual and/or automatic line breaks.

All of this makes it even harder for heuristics.

I want to stress that these are not bad practices - many of them have long and detailed traditions (e.g., commutative diagrams). They are simply print traditions with no consideration for the web, let alone accessibility.

interlude

On the web (and in many publishing content / production pipelines), abusing HTML markup is frequently favored (i.e., text superscripts, tables, simple vertical alignments) alongside low quality (usually GIF) rendering for inline math and high-quality (usually PNG) for display content. Frequently, only the 'problematic' parts are rendered as images leading to poor layout (e.g., tables with some equational content and a text label in lieu of properly labeled equational content, HTML scripts with graphics in either base or script position). Accordingly, content providers have a long history of "optimizing" their content for these approaches (e.g., STEM publishers have really terrible XML workflows stripping out as much complex markup as possible). That content is in some ways lost forever (because it would be cost prohibitive to re-key it).

Non-visual print equation layout

In several countries, print equation layout has some form of non-visual accessibility tradition.

The US traditions are dominating in this context since MathML was developed largely by US companies for a US audience.

For print traditions in the US, the most well-known methods for non-visual presentation for equation layout were developed by Abraham Nemeth - nowadays known as the MathSpeak ruleset for voicing and the Nemeth Braille notation for tactile presentation. A critical point is that both sets were designed for human creation. MathSpeak, to enable a non-expert reader to read mathematical publications to blind users; Nemeth Braille for a specialist braille transcriber to transcribe (and a trained reader to read).

If you can catch him, Volker Sorge (who implemented support for both as part of Speech Rule Engine and MathJax) is happy to go into much detail telling you how neither MathSpeak nor Nemeth Braille can be produced from input without extensive heuristics. The rulesets are in fact not properly specified and can be contradictory.

My impression is that this is by design - these rulesets could assume a human orator/transcriber who can adjust rules on the fly to enhance the simplistic heuristics. Even without understanding mathematics, it's fairly easy to make a change on the fly, e.g., after initial feedback from the user that in this particular pattern the superscripted 2 is not "squared" but, say, a row or column vector.

It's probably worth noting that Nemeth Braille has not been revised since the 1970s (though a revision has finally started a few years back). It is a specialized Braille notation that describes visual layout and only partially linearizes the output (e.g., fractions and scripts are linearized while tabular structures are not), leading to many problems as contemporary refreshable braille displays for computers are single-line devices. And of course, if you're not a Braille user, then none of it helps you.

heuristics are bad, non-recursive ones worse

At this point let me point out that heuristics are something that web accessibility eschews; heuristics are only encouraged to recover from errors (e.g., turning invalid documents into a valid ones, making sense of authoring or connection errors, dealing with legacy code like table layout).

Accessibility on the web revolves around the so-called "accessible name" which is calculated for each element in the document. This calculation is rather complicated but at the heart of it is Step F: the accessible name of a node is accumulated from the accessible name of its children. From the end users point of view, you tend to get some additional information (such as the role of the element) added by AT. And that's about it.

Print equation layout frequently does not allow for recursive naming. The heuristics necessary to guess a non-visual presentation have to frequently analyze large subtrees to make sense of things.

A simple example is binomial notation,

To make things worse, in many print equation layout systems this notation is realized via fraction primitives by removing the fraction bar (e.g., TeX, MathML). If you were to calculate the description you now have to decide what to do with a fraction that lacks a fraction bar. Now add to this mix the Legendre symbol

We can also go back to our script examples from earlier - for 2 and -1. While

MathML is even worse for this, as it is a stratified format for rendering purposes. With TeX you can at least have author macros to try to make sense.

Authors, especially on a research level, invent layout that requires new heuristics - both large and small. For example, they create custom glyphs (such as blackboard bold Greek characters) or they invent notations as grapheme-like tikz diagrams which then get used like any other element of a larger expression.

Historically, such inventions coincide with naming. Jeff Miller collects several historic examples (such as nabla). Yet, naming is not always invented alongside notation if you recall the Legendre symbol once again. [Authors also regularly just hack layout badly (e.g., \mathop{l\overline{og}}) but that's technically speaking a different problem.]

Authors also intentionally hack things to work around traditions. A while back at work we ran into someone apparently abusing amsmath's sideset macro in something like \sideset{}{^*}{\sum}_{a\mid A_y}. We only noticed that because MathJax had improved sideset to be more accessible which changed the rendering (and introduced regressions). Upon investigation, it turned out we had a lot of similar papers. Even better, all of these authors used sideset consistently to get a superscripted sum that would still have a "movable" subscript.

In other words, authors clearly want a certain type of layout that goes against traditions; they have good reasons to do so. Heuristics trying to make sense based on those traditions suddenly break as well.

This is a perfect example how traditions hold us back. They are too rigid - you can't have "partially moveable limits" without resorting to hackery. And once you have that kind of a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

MathML

MathML does not provide sufficient quality, neither in theory nor in practice.

visually

Practically: visual rendering in browsers is poor, buggy, hard to work around. It is not maintained by browser companies and never has been.

Bugs range from mildly annoying to problematic to terrifyingly bizarre. I stopped noting them publicly; it's too much fun to check every few years that even basic bugs do not get fixed or even reported.

Theoretically: visual rendering is not actually specified (thought here is a new effort to change that, making all existing MathML renderers invalid and breaking content without care).

This is where they are after 25 years of MathML, 15 years of MathML in HTML5, ~10 years of MathML "support" in Firefox, ~8 years of MathML "support" in Safari, neither of which are due to actually Mozilla or Apple spending resources but co-opted volunteer efforts. No amount of Igalia newspeak will change that fact. [Apologies to all the wonderful people I've met from Igalia - the MathML people are not a good look for you all.]

Optimistically, I'd wager it will take a good decade to get reliable visual rendering quality. Certainly, CSS, SVG, HTML and ARIA will all move faster and help tools like MathJax even when they're not trying.

In any case, the handful of people behind the implementations seem unable to grasp what the real life problems are so they live in their little bubble insisting that repeating "but it's a standard" does anything for users.

non-visually

MathML captures abstracted, shared concepts of print equation layout traditions. It suffers the consequences in terms of non-visual rendition.

Practically, MathML support is poor among screenreaders and is non-existing in"simpler" assistive technologies (with way more users) such as "read aloud" features in browsers, voice assistants etc.

Only three screenreaders formally claim support and their support is limited, buggy, and of poor quality - and the pieces are minimally maintained by AT companies. Brian Richwine's talk at ATHENs documented many cases, e.g., how some ATs don't voice "end fraction/script" causing confusion (my favorite part was the anecdata form Apple support saying there's just not enough users to warrant fixes.) [Though admittedly, I have yet to see someone exhaustively testing them. Nobody is paying to test that, not even publishers who have a vested interest because the "experts" say "just use MathML".]

In addition, the user experience of what little support screenreaders provide is often questionable, e.g., JAWS will not read larger MathML fragments but just announce the presence of a math fragment; users have to then open a separate viewer application to actually read and explore the expression. [Fun fact: this is called "Math Viewer" and actually uses MathJax for visual rendering, leading to significant differences from the browser.]

Similarly, VoiceOver on iOS will open pop-ups for exploration of MathML fragments, creating a separate context and confusion. NVDA needs third party plugins to do anything and has no visual component (i.e., highlighting while exploring)leaving non-blind to guess what is going on.

I don't think it's enough accessibility support in the sense of WCAG conformance.

Theoretically, MathML cannot be accessible in the web's sense. Heuristics must be applied and now you (frequently) have 2 problems - your MathML must be hacked to work visually and then you might still have to hack around heuristics gone hawywire.

Back when I led the W3C Math on the Web Community Group, we had fairly productive discussions even with the MathML people and we had strong consensus (with them) that MathML inevitably requires extensive heuristics to provide non-visual (voice, tactile) renditions. Nevertheless, the same people later turned around again in wider W3C discussions, going back to the spurious claims that MathML is the only viable accessible solution.

The sad part is that the W3C's TAG fell for it (and will fall for it again). My guess is because they just don't care to dig deeper - and why should they? Nobody wants to and anyone sensible will just use MathJax.

Other aspects

localization

Another argument sometimes mentioned by MathML people is that MathML can be localized automatically. While that's true to some degree (e.g., Speech Rule Engine can create MathSpeak in a few languages), the benefit seems a questionable if the locale does not match the contextual language, say, coming to an article in Arabic and getting an equation localized in Korean. At the very least, I'm unaware of research substantiating a positive effect.

In practice, the available localizations in AT is quite limited and pretty undocumented. This is even worse for Braille.

There are obvious obstacles for localizations. Many equations contain some text elements which would not be localized. Similarly, common terminology has different localizations/abbreviations. For example,

- sine as "sen" (ES, IT) or "sin" (EN, DE)

- in geometry SAS/ASA/SSS (EN) vs SWS/WSW/SSS (DE)

- sin^-1 (EN) vs arcsin (EU) (etc)

- repeating decimal notation (above, below / arc vs line)

- open intervals as

(...)or]...[ - any operator names the authors may introduce.

While layout-relevant terms might have suitable automatic translations (e.g., start/end fraction), layout traditions can also differ across languages (long division, matrix notation, integral notation).

Nobody stops to ask: should we do this? As print equation layout is fairly meaningless without lots of context, it's difficult to imagine a reader that would read content in a language they don't understand enough to make sense of generic information like "begin/end fraction".

The "Don't worry about it" argument

The MathML community likes to say "don't worry about the complicated markup, MathML is something that should be generated, not handwritten"

This is a strange statement full of falsehoods.

For example, MathML is also advertised as "something you can edit without understanding it", e.g., while copy checking content, if an editor spots a symbol that does not match the (author) PDF, then - thanks to the structured XML markup - they can fix it without understanding.

This marketing example also indicates two problems: conversion is not "easy" but riddled with errors, and having an "agnostic" markup is actually a boon here - to any production person trying to fix a mistyped macro in TeX sources: I see you.

But of course the same would be true for span soup since the markup really doesn't matter much here. Though actually, semantics tend get in the way while layout information would be useful. (Again, it makes actually sense for XML production to have a layout focus.)

Similarly, as described before, MathML supports "moveable limits" (including magical dictionary-based behavior). These features show how important it was for the MathML community to be compatible with authoring traditions instead of focusing on the "pure" layout. If you generate it anyway, why not make it precise and avoid this?

Finally, this line of argument is self-defeating. If the whole point is to convert from some kind of "real source" to MathML, then it's just as natural to convert from that "real source" to HTML or SVG.

Why have an extra markup system that requires an extra rendering process when you can just use what's already much better supported?

Limited support for MathML

Among screenreader, only Apple VoiceOver and Vispero's JAWS claim to support for MathML. In reality, the implementations are full of bugs and gaps. Bug reports are rarely responded to, far less fixed. Apple has essentially communicated "it is what it is".

Nemeth Braille support has relied on the liblouis library - which recently discontinued its support of it; liblouis only ever converted MathML to the Nemeth/UEB and German/Dutch/Flamish families braille notations - and it did so quite poorly. [No, the new "cat" on the block doesn't count either. Old wine, new bottles, just as rusty.]

More importantly, no "light" assistive technology supports MathML,e.g., "read aloud" features in smaller assistive helpers, in epub reading applications or in voice assistants (Siri et al, e.g., when reading out web content). This lack of support impacts the largest portion of users, since these tools are much more widely used than the more advanced, full-fledged screenreaders like VoiceOver, JAWS, and NVDA.

What do we do to address this inherent lack of accessibility?

Print equation layout is inherently not accessible in the sense of the web. MathML is a red herring as it (at most) aims to reproduce accessibility traditions from the print era but inherently cannot reproduce it well since those traditions relied on human operators(orators or transcribers). It also only works for English and, it seems, really only for Nemeth users.

I approach such problems by looking for guidance regarding the web in general. The web's grain, if you like.

The web's core principles

"Users before author before implementors before theory"

From the W3C design principles:

User needs come before the needs of web page authors, which come before the needs of user agent implementors, which come before the needs of specification writers, which come before theoretical purity.

What do users want from print equation layout? And what do they actually need?

We simply don't know.

Yes, most countries do something at the school level. But actual research is barely existent; what little there is, is usually limited to small groups and all the biases of simplistic educational studies.

My impression has been that there are too few AT users among the mathematical community - support is so poor, few make it to college let alone research-level. Accordingly, few have both the skills and the luxury to think freely about the problem. (T.V. Raman is one of the few exceptions and I'm still grateful he gave Davide and me the opportunity to work with the ChromeVox team for a bit - and to meet Volker Sorge who was on sabbatical at Google Research back then.)

Anecdotally, the most consistent feedback I've seen in educational studies comes down to "I want it to be read like my teacher/prof reads it in class". That sounds an awful lot like users want to have what authors want to say, and matches the core principles pretty well. It's one of those "did you need a study for that?" moments (yes, we do) and yet it shows how flawed the current approaches are. Yes, it's a common paradigm that authors should enable AT users to customize their output. But if you take away the author's ability to express themselves, are you really helping users?

Assuming I'm wrong in my assessment for lower level equation layout: for mathematically heavy research material? There's absolutely nothing to base an opinion on.

Those users probably want TeX annotations because research-level users very likely know TeX syntax. But is that what they need, e.g., when exploring a complex expression? [Fun fact, some European communities favor presenting TeX strings in Braille - starting from first grade.]

interlude

This discussion is usually skewed by two major factors: US users and blind users. As with most of the web, the US dominance has led to people ignoring other factors. If it works for US users, it's fine, amiright. So the limited MathSpeak and Nemeth implementations in MathPlayer were enough to woo the US blind community and its influence wooed the rest.

To take an example. Blind users (especially students) need to write assessments using the tools their classes require. If they need to use MS Word, they'll need something to paste into Word. MathML was originally conceived as just such an exchange format for print equation layout - abstracting the minimal common ground so that each engine could reasonably present it.

However, the authoring problem requires conversion. This easily goes haywire. For example, Libre office's "Math editor" digests MathML but converts it into its own linearized (~Asciimath like) syntax. And while it includes MathML in its file, that MathML will be generated from the linearized format. This is a process full of bugs.

MS Word does the same thing but has a custom XML format for print equation layout. Same approach, same problems. It doesn't help to add more formats (such as TeX-like input).

MathML-based wysiwyg editors exacerbate the problem (as wysiwyg is wont to do) since they cannot easily discern logical structure of input // do not make it apparent to users that they're doing something really terrible (e.g., inserting random whitespace, flip-flopping font choices).

However, if you are a blind user who knows Nemeth well, then that conversion process might just work sufficiently well for you because things were designed just for this use case. Ergo, you will say it's great and your influential community will prevent any discussion about whether this is actually a good trade off for other user needs.

At ATHENs earlier this year, all speakers I heard included at least one statement along the lines of: "our successful students are those who know Nemeth". Clearly, it's good that Nemeth helps students succeed but in the words of a spaceship captain: "Not good enough, dammit, not good enough".

The reality of all users is: the web is fairly bad at being copy&pasted elsewhere. And that's an interesting, complex, and very broad problem. I'd love to see more movement in this direction but I don't think it makes sense to make copy&paste to MS Word a requirement for realizing print equation layout on the web when nothing else on the web can do this. (Pasting SVG into Word anyone?)

[Repeated conversion tends to be lossy. From my limited yet painful experience of editing conversion results, I doubt it will be great if you went back and forth across print equation systems for a bit; if I cared enough, I'd test that hypothesis.]

Ultimately, Braille is a print technology, and in the context of a refreshable display there isn't even a page, let alone a multidimensional presentation that a dynamic webpage can provide. Again, this is a broad and interesting problem, again print equation layout is not a great case for special treatment.

Similarly, Unicode math alphabets are a print technology. It makes sense in a print context to separate out codepoints that have very special fontface requirements. They work fairly terribly in terms of non-visual rendering. For example, I once tested the string ϕ(x)=∑ₖⁿ xᵏ and it came out as "open paren x close paren equals n-ary summation n x" (JAWS) or "x equals n-ary summation superscript n x" (NVDA) and "phi x equals to the power of n x" (Chrome speech synthesis). Yay us. Now you might argue that in the right markup, voicing could be different, e.g., automatically more verbose. And that's an excellent point - but I would couner that math alphabets are far from the only Unicode characters with these kinds of problems - emoji for one are even more prevalent than math alphabets to fill account names or social media postings - and a better solution would be a general one, not "math markup".

Another quirk of the accessibility traditions around print equation layout is what layout information is exposed. Font variants, upper/lower, under/overlines are all exposed - yet color is not. Why? Likely because print traditionally doesn't use (a lot of) color out of the pure necessity that color print is not readily available. But that is not stopping authors; color is a useful and beautiful tool. Of course, it's "obvious" that non-visual media won't present color well but neither will it present different typefaces well - and somehow that was ok with everyone. This is particularly strange, when you find dedicated syntax for "mathcolor" with no effect.

What to want for authors

I want to give authors the ability to express themselves well.

And authors want to do that.

Just look at any "list of symbols" in a monograph, e.g., from this combinatorics book

Despite using very ambiguous terms, the authors clearly have a strong intententions.

I want authors to bring their intententions into the process.

We can (barely) do that with Speech Rule Engine. We cannot do that with MathML.

What do you want for your users?

I want to take responsibility for my content.

I want to provide high-quality consistent, robust rendering for all users.

I want to provide visual layout that is robust against font issues (especially onepub).

I want to provide speech and braille alternatives.

I want to provide consistent, reliable, robust exploration.

I want to be able to fix issues.

I want to be able to provide additional features (e.g., convenient access to TeX sources, customization options).

What do you do?

I usually provide high-quality visual rendering using MathJax's SVG output, alongside the high-quality heuristics in Speech Rule Engine to generate non-visual rendering.

I also generate fully explorable layout and descriptions that are the same for everyone everywhere. They are robust enhancements with solid fallbacks. If there is a problem, it is my fault, not the user's. And if need be I can fix it in post.

I tend to use the MathSpeak ruleset for descriptions meant for voicing because MathSpeak doesn't attempt to be as "smart" as other available heuristics (which target school level mathematics).

I use Nemeth Braille because content is primarily in English. Arguably, Speech Rule Engine doesn't have any support for other Braille output so I accept that I need to use Nemeth for other languages. I'm not beyond using TeX as quick alt text. If I want more, I'll try to help Speech Rule Engine get funding.

I make sure that speech descriptions work with all tools - from full-fledged screenreaders and simple read-aloud tools. If there are issues (e.g., a recent VoiceOver on iOS regression I ran into), I can work around it.

Yes, the ARIA technique for exposing Braille alongside speech-optimized text is cutting edge and not widely supported yet. But they went from editor's draft to full browser support in 2 years and they help much more than just print equation layout.

I often embed TeX sources that automatically copy&paste when you select things; it's a nice bit of magic under my control.

I set things up so as to allow for additional options to expose various formats (e.g., populating everything with TeX or loading full-on client-side MathJax).

I do so with intent and knowledge of the problem space, the capabilities of the solution I built and the flexibility to help users.

interlude

Some good old whataboutism:

What about electrical engineering diagrams? Same garbage print stuff but at least nobody pretends to cook up markup. Take diodes - their symbols for their types are basically letter like. Shouldn't we have those in Unicode?

What about chemical markup? ChemML is another wonderful XML abomination.

What about, again, music notation?

Should all of these be first class citizens on the web, with separate rendering systems to adhere to their particular (print) histories?

Tangents

copy & paste

The MathML community will frequently point out how "easy" it supposedly is to copy&paste MathML around.

The reality is that extremely few applications accept MathML, it's a cumbersome process, and MathML is dropped in the end, converted to whatever internal format is used by the target application.

The primary reason why this myth holds is that MS Word digests MathML. However nowadays, MS Word also accepts (reasonable math mode) TeX when pasting into "equation fields" which shows both the limited usefulness of MathML as well as the pervasiveness of (math mode) TeX. And of course Word uses its custom markup syntax internally (and its home-grown technology for braille and voice rendering instead of whatever ATs provide).

More importantly, while copy&paste is a worthwhile challenge, it is also a general challenge with web content. Copy&pasting website content into any kind of text editor (word processor, email application, TeX sources) is very poorly supported in general. While headings might survive, even something as simple as a list can break, tables usually break and "true"web design (e.g., CSS grids) does not survive. Even (inline) SVG content is not supported widely (despite being a well-supported, self-contained graphics format).

This is not at all surprising given how most of the targets are meant to create print layout - and struggle with web layout. Why then should equation layout on the web be less complicated than the rest? Instead of insisting on broken technology (like print equation layout and specifically MathML), it would be better to think about the more general problem that affects everyone. We have to anyway and a niche solution does not move us forward (yes, HTML v3 did have it wrong).

authoring and recreating

Related to copy&paste is the area of authoring and recreating print equation layout.

Let's go back to the example of matrix determinants. Both det(A) vs|A| would be voiced as "determinant of A" yet their authoring is quite different.

Sometimes, readers have to (re)create content to match someone else's example (e.g., in any educational setting). Again, this is a general problem (color vs colour). For text, AT usually provides character-by-character navigation (incidentally, I'm not sure about graphemes more generally). For print equation layout this is naturally trickier: on the one hand, we come back to the idea to "just" give layout information, on the other hand layout may be insufficient (e.g., table-like).

Voice input/output

Voice input is becoming an important aspect of how users interact with web content, both using AT (e.g., in combination with Dragon NaturallySpeaking) as well as using general purpose tools such as smart assistants (Siri, Alexa etc).

Despite funded efforts, there has been not even light progress for enabling print equation layout by voice input.

Audio and Video Captioning

Providing accessible audio and video media requires captions, in particular transcripts, subtitles, and audio descriptions. For content rich with print equation layout, automatic conversion requires voice recognition, image analysis, and conversion to speech (e.g., a mathematical lecture with equations on a blackboard that the speaker discusses). Since the standard formats (e.g., for subtitle functionality in a video player) require plain text, MathML is of no use here even if it were an adequate fit for how people speak. In addition, there are no tools nor traditions around "speaking equation layout" in such settings.

Reversely, there's audification. Take Google's AI-driven audio book narration. I doubt it'll do print equation layout anytime soon (by which I mean: ever).

Search

Despite decades of research, search around MathML has never provided tangible benefits despite clear user needs to discover existing results both to avoid and identify duplicate research. This is true for all of the ever expanding STEM fields.

Springer's discontinued LaTeX search or zbmath's MathML based system are good examples of this failure. A sizeable research corpus revolves around analyzing MathML fragments, yet no actually useful system is available.

Progress

Here's a very personal opinion: the MathML people have actively worked against progress for equation layout on the web, and STEM content as a larger issue.

Why do I say this? Because anyone who has followed this area as closely as I have in the past decade or so (which, alas, is barely a handful of people) know that it's the MathML people who insist that MathML must be implemented at all costs, actively damaging other approaches, even approaches with better results for users.

To the purists, MathML is more important than users, authors, and browsers.

As a result, projects that made actual progress (like MathJax, mathlive, hell - even KaTeX) are in danger of losing support from their communities because people are being told "you must use MathML". [Don't get me wrong, I can gripe about these projects, too, but at least they move.]

All the while, there's no indication that MathML development will speedup at all, even if Chrome ships the new, cut-down, incompatible spec.

So if you ever again complain about the lack of improvements in this space, blame the MathML people. They are to blame. We could have made many small improvements to the platform that would have benefited everyone if the MathML people hadn't killed everything that didn't suit them and drove away anyone who didn't agree with them.

Reversely, MathML is being held back where it actually shines - XML print production. There's so much useful print equation content to consider for XML workflows (tikz alone!); extending MathML would be natural here. Instead, even the XML people get nothing (or worse - a cut down spec they can't use until JATS adopts it).

I wrote earlier that "web equation layout" is not something that exists. So you might say, what's the problem? I think the problem is that we might get stuck, in a bad way. Here's quote from On Mathematical Symbols in China (again, thanks to Christian's Interesting Esoterica).

Ancient Europeans struggled with fractions because of the use of tedious Roman numerals, so ancient Europeans were weakest in algebra. However, when Indian-Arabic numerals were introduced into Europe, four operations in Europe were simplified. [... As] a result, algebra developed rapidly. Similarly, China's ancient mathematics failed to form a perfect symbol system and were stagnant because of the limits of the counting rod, resulting in not only a lack of the axiomatic system, but also the absence of symbolic algebra, analytic geometry, calculus and modern variable mathematics in China. Naturally, to move forward it was necessary to break barriers and to get in touch with international standards and to forward to symbolic mathematics. This shows that the extension and development of any prosperous culture cannot be confined to the boundaries of that nation, and it is hard to create a complete and rich symbol system independently and separately from the influence of other nations and the outside world.

I think the web should not be confined to print equation layout. We should not want to get stuck replicating a limited medium in a much more versatile one.

MathML is the zombie of web standards. Each decade brought 1 additional, differently broken implementation (first Firefox, then Safari, soon Chrome). The new spec for Chrome will render a lot of existing content unexpectedly or not at all, but it will be the author's fault - how clever of them. XML people will have even more "fun" getting their content to work on the web. (Or, more likely, just continue to use MathJax which just keeps getting better instead of worse.)

Bugs in those three disjoint implementations are, of course, aplenty; I find a new one every time something forces me to look at native MathML implementations, some are ridiculously bad (wiping out HTML content is one of my favorites) and most bugs go for years without bugs even being filed (remember when Safari didn't draw fraction lines reliably for over a year? No, you don't because you don't use it and nobody even filed a bug).

For the web, the best case scenario is: nobody cares and nobody uses it. It will become the new font/center/marquee or whatever.

Even if the MathML people were interested in moving the layout facilities into CSS, we'll get, at best, something like CSS tables. If you don't know the "joy" of working with CSS tables: to this day they are not able to suitably realize HTML table layout, they were super buggy for the longest time and are still buggy in many edge cases (despite years of active improvements). But most of all: people realized they actually needed something completely different, i.e., CSS grid, flexbox, and container queries.

Accessibility wise, the shoddy implementations in JAWS and VoiceOver will continue to barely help English speaking blind users. Soiffer will try to push his weird MathPlayer clone into every AT so that he can continue to claim patently false things. No "intent" in the world will make print equation layout accessible in the sense of the web. Nemeth users might eventually get what they want - the rest? Not so much.

In other words, users will continue to find themselves out of luck. But hey, "it's a standard". They made you beg for it, then they begged you for money (instead of Apple and Google); now you have something you don't want, something that doesn't work and something that cannot work. It's what you wanted, a "standard".

I think MathML (this of course means: its community) is fundamentally not willing and not able to be a positive force. It's "MathML or die" all the way. The zombie standard continues its shambling walk.

interlude

The future will be different from what you expect. The other day/month/year, our oldest started learning the piano. Of course, this means learning musical notation; it's one of the benefits, I'd say. But it's (inevitably) hard to motivate.

So being a stupid internet person, I searched around for fun apps that teach the piano. I found apps that, shockingly, didn't really use traditional musical notation. Instead, they had some barebones resemblance (I'm guessing to enable later learning) but they took things in another direction by leveraging the medium, i.e., modern mobile applications.